Why did it take a crisis?

In 2015 I campaigned for months before finally having to fly to America and persuade a reluctant CEO that software developers could wear jeans to work.

In 2018 I watched the development of a working from home policy that stretched to about five pages of definitions and restrictions and had at least two authorisation levels.

Over two short and hectic months in 2020 we’ve grown used to seeing into colleagues homes as they work in pyjamas, dangling children or pets on their knees and everyone is sufficiently convinced that this change is forever that PwC report ¼ of CFOs reducing expenditure on real estate and Barclays say they may never put 7,000 people in a building again.

The potential of our desktop to facilitate this change has been there for a decade. Office space has been unreasonably expensive for longer than that and commuting has been a burden on families and the planet for even longer.

Why did it take a crisis to force us into something so clearly rational?

I guess the answer is humanity. Evolutionary biologists talk about ‘punctuated equilibrium’ where long periods of stability are followed by radical change; Ernest Hemingway tells us the same in ‘The Sun Always Rises’:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

And Hans Rosling, an epidemiologist, writes that we believe progress is continuously smooth and that some things will always stay the same despite our experience that both these assumptions are always wrong.

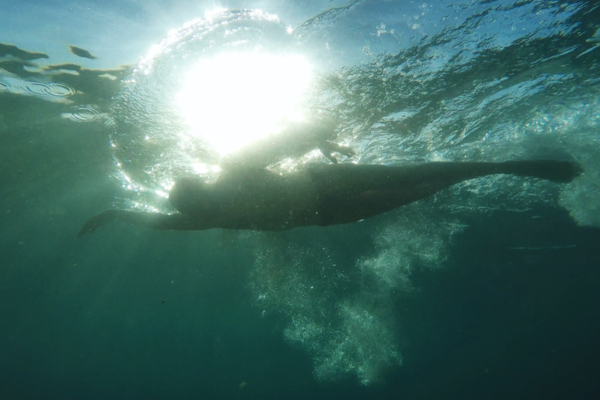

And where we ‘knowledge workers’ are allowed to do our work is only the change most visible to us, the tip of the iceberg, first order change.

Because this crisis begs other questions which have been on the ‘too difficult’ pile for a long time.

What is the role of the manager when thinking as old as Demming in the 1950s and as contemporary as Agile demonstrate that self-managed teams function better without interference?

What is the role of learning and development when we no longer fly around the world to gather in hotels and form teams over wine and conversation?

What is the opportunity to engage the whole person at work, the emotional, spiritual, intuitive wonderfully human self as well as the occasionally rational person we’ve pretended to be at work now we engage surrounded by our homes rather than our offices?

What do we think about Purpose now that the inequalities around us we’ve accepted for so long make us suddenly, shockingly, gratefully aware of the true value of ‘key workers’?

In the 2014 Ritesh Batra movie, ‘The Lunchbox’, Shaikh tells Sajaan:

‘Sometimes the wrong train can get you to the right station’.

May this be such a moment.

KJB.