Viral Rhythms

The daily life of a lecturer at a university some seventy-five miles from your house is a life of odd rhythms and the unsettled normal. One day your alarm will go off at 5:50am, to hit the M40 in the opposite direction to all the traffic streaming toward London, to walk into a yawning classroom at 9am and startle the collected faces of youth arranged before you with tales of radical modernist poetics and dashing narrative experiments; then another day that same week, you’ll pour out your coffee and settle down to write MA lectures for the late evening class, or research the intimate details of the life of, say, Wyndham Lewis, modernism’s resident scoundrel-genius.

Because no two days are the same, by the time I woke up to the reality that Covid-19 would bring a significantly disrupted life into the heart of England, I was more concerned for others than myself. I could work from home; I could continue to research, or mark papers, and so long as I could secure some rolls of toilet paper and keep clear of the virus itself, my inconvenience would be minimal. There was no disrupting the rhythmic beat in my life; no ‘normal’ to fear its disappearance.

But then rhythms never exist in isolation – a beat is just a beat, until you put it, rather unexpectedly, next to a competing set of patterns in noise.

My kids, my wife, my neighbours, their dogs, or students suddenly thrown out of their depth and desperately in need of something new – these were the noises that began to influence my normal uneven rhythms. And bizarrely, they brought new order.

When my son first heard that schools might be disbanded, he thought it could be pretty good. But his secondary school is highly organised, even driven by a mania for performance, and when the kids were sent home, the classes went on, online, as before. He was still supposed to sign in for tutor group at 8:40am and was on a regular timetable until the school day’s end. He didn’t have to wear his tie, but the school mufti rules still applied, and apparently any moment they might ask for you to share video to check that you hadn’t fashioned your hair into a Mohican, that you were actually really there.

He was always really there, all morning, waiting for that fifteen-minute break at 10:50am, as with any school day. And all of us, pulled together into one house – two workers, two students – we all started to look forward to that same break. We’d gather in the kitchen for a bit of apple, an update on how the morning was going. We would see neighbours we had never seen before, every day, walking past each morning to walk some dog newly energised, it seemed, to the viral routine of 10:50am walkies.

My wife and I were used to working from home, but our schedules changed – becoming one schedule. We would all hold off on lunch until 12:40, which was officially secondary-school lunch time. At 3:05, with my son’s classes ended, it was biking for the kids and running for the adults. This was regimented, regular.

The same Morrisons or Ocado truck would stop at the same houses, in new patterns, with drivers we’d learn to recognise. There’s one house on our road that gets regular visits from an ambulance, which stays for several hours, then departs, silent and without lights. We don’t know why, but it’s no longer news. There’s some tragedy in that house around the corner, I guess, slowly unfolding on odd days, but the outward evidence is only another rhythmic part of our daily pattern.

There’s another neighbour who looks a bit like Ben Kingsley who walks down the road, just beneath my window, hand in his pocket, every morning at 11:55am, then returning half an hour later, no hand in his pocket, Tesco bag for life by his side. There’s no Tesco half an hour’s walk away, so I don’t know where he goes, what he buys, what his name is or where he lives, exactly – but I’ve learned to count on him. My stomach knows, when I see him returning up that road, that it is twenty minutes to lunch – a new bio-rhythmic, autonomic response caused by the sight of a stranger.

We’re all strangers to these new routines and new patterns, but we’re somehow newly in rhythm. Not just my family, whose bodies have all come into sync, as if by astrological gravitation. No, the whole world.

The Guardian, for instance, has recently reported on the disappearing vibrations caused by human activity, as normally picked up by seismometers. Ian Sample concludes: ‘The dramatic quietening of towns and cities in lockdown Britain has changed the way the Earth moves beneath our feet, scientists say.’ According to the British Geological Survey, the so-called ‘cultural noise’ of human activity and its persistent impact felt by the earth right down into bedrock has faded, and the subtle spikes of our seismic impact have flattened.

I can feel it. I’m measuring out my lockdown in the commuting miles I don’t have to cover – in that stretch of M40 and A43 that is no longer full of my ‘cultural noise’.

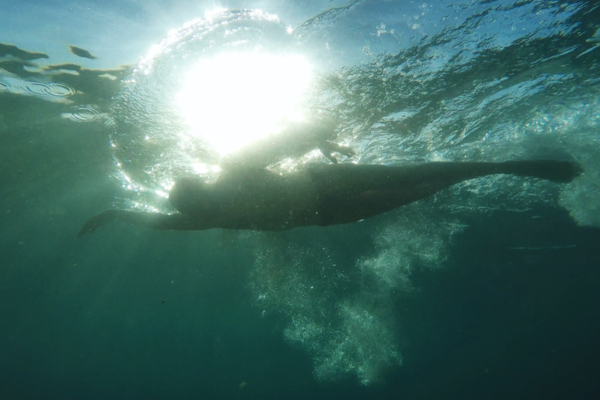

So the Earth is quieter. We’re not moving, not quite as much, and we’re maybe no longer leaving seismic waves in the wake of our bustling activity. But it doesn’t mean we’re still. It doesn’t mean those rhythmic waves don’t still roll – or maybe they’re just new ones, newly rolling. And we’re still trying to determine their frequency or their patterns, what they may mean or where they may lead. There’s still cultural noise. From the Sainsbury’s trucks dropping keeping the neighbours in food to the ambulance that quietly persists in treating some unspoken harm; from the hedgehogs visiting the garden nightly to the bald man walking past my window every single day at 11:55am; from the utter exhaustion of an NHS nurse to the pounding beat of my daughter doing PE upstairs in her bedroom – we’re all finding new patterns, new rhythms, new normal waves of activity. And if my family is an indication of the future, the rhythms will sometimes be even more in sync, not less – the new ‘cultural noise’ may yet make real music – as well as leaving hurt silence in the deep places of history.

Rod Rosenquist is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at the University of Northampton. His research includes a project on modernist life writing and he teaches creative nonfiction, as well as leading an MA in Contemporary Literature.