Eavesdropping

Imagine you would be a detective, conducting a secret surveillance operation. Listening in to people would be an indispensable part of your job, not an irritating fact of being in the same train carriage as an inveterate cell phone addict.

Would you enjoy eavesdropping? Chances are it would be just another part of a job to do. Hours and hours of tedious sound, waiting for a turn of a phrase or a code-word signalling that, finally, you may hear something topical as opposed to less enlightening minutiae of someone’s days.

Imagine you would be a historian, browsing reams of texts about exactly that seeming tediousness – minutiae of someone’s days in a search for a structure, a pattern, the one enlightening reflection of society on the rippled surface of an individual life.

But what if you just happen to hear snippets of other people’s lives? Here is where the forensic specialist and the historian meet – the snippets are tantalizing, sentences broken mid-air; you need to hear more, to find other traces; the less they say the more you have to hunt. The everyday eavesdropper has the advantage of being a casual witness to fragments, free to fill in the voids. As a flaneur or flaneuse, the everyday eavesdropper strolls through the city, and browses other people’s lives like shop windows. Except the snippets of lives are the very opposite of shop windows – seldom well-dressed and ready for inspection, welcoming your curious gaze and inspecting auricle.

The sea of humanity can be irritating, but the quarantine did change that perspective. Snippets of the life of another became welcome as windows on the world beyond. ‘I am really glad I have to spend this time in Oxford now, imagine being in a big city’ … pronounced with an accent unmistakably located in the shadow of Empire State building, now relocated under a horse chestnut tree that has just burst in flames composed of thousands of orchid-like blossoms. A glimpse of a New Yorker in University Parks, feeling safely ensconced in the greenery as opposed to the forest of concrete towers?

‘I do not know about their perspective on the project’: the sentence is floating across the meadow in a cloud of pollen. Life is still going on! People discuss projects, and work, and strive to have a future regardless of the irresponsibly relentless gloom peddled in the news. Every signal count to say that the nausea of fearmongering is not winning everywhere.

A windy day steals sounds at people’s mouths. It is evening, shafts of sunlight fall between houses and trees and the wind billows white robes of a monk engrossed in a socially distanced conversation at six feet with another man who is clutching at his windproof jacket. The white cloud of the monk’s habit highlights the contrast - practical ungainliness of the jacket versus sculptural qualities of the habit.

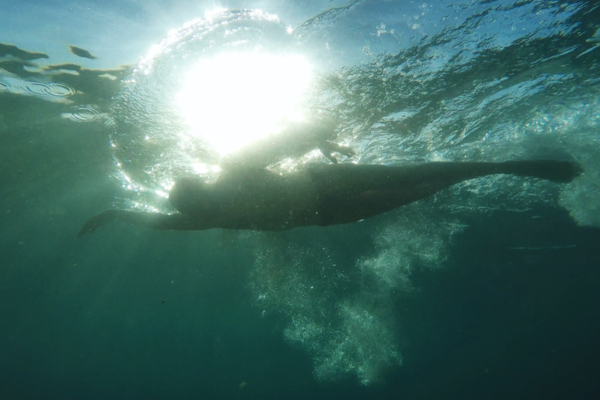

A red setter chases across the lawn, and his freedom is a painful reminder. But then, are we ever truly free? What sorts of mental lockdowns are we ready to impose on ourselves? Locked in our inner worlds, snippets of other lives just a nuisance again, a sea of sounds to swim through in a railway carriage. We need to be free again, but then, when the physical distancing begins to wane, how much remoteness will descend?

Anon.