Beginning of a memoir

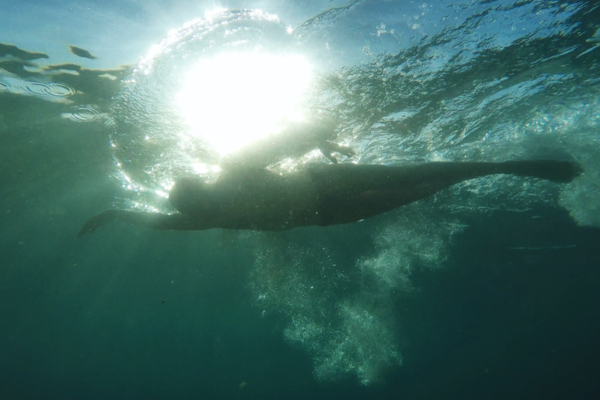

First came colours. Blue and yellow building bricks. A crude, blue wooden money-box of that treacly, nursery blue so popular in the 1940s, with a blob of a yellow chicken on the front. Beyond the window-bars, when you lay on the nursery floor, the sun shimmered towards you like a tin-lid swaying downwards through a basinful of water. If you shut your eyes then, you saw purple with green specks; and if you held up your hand between your eyes and the sun, the closed spaces between your fingers glowed orange like the elements of an electric fire.

Stripes were exciting. A striped cushion, a barber's pole: they all meant something.

Colours on their own were one thing, but their relationship with one another suggested all sorts of hidden meanings. Yellow meant sunlight, openness, freedom, against the blue of a blue sky. ‘Yellow is my favourite couleur’, I announced in yellow wax crayon on the white brick outside edging of a downstairs window belonging to the room that passed as a playroom. My parents called this the junk-room, a fit enough expression of their feelings about their present way of life. They were only camping, playing at having a house, which my father’s father had bought them after I was born and which my father had long since decided he hated. Keeping up appearances would have cost them unnecessary effort on top of the strain of sheer survival. (It’s Only Temporary, was one of my mother’s favourite expressions, together with Any Old How and Muddling Along Somehow.) In between the pencil drawings of excreting bottoms with which we children decorated the peeling, distempered stairs wall, I would also scrawl my name and age (5) with a corner of my piece of chocolate when sent up to lie down and be out of the way after lunch.

There were no pictures in our lives, apart from holy pictures interleaved into missals, a large, signed photograph of the previous Pope but one, and some odd throwouts, mainly anaemic nursery pictures (The Piper of Dreams, In Dreamland) that nobody else could have wanted. Colours, however, were everywhere, even in that allegedly drab period following the end of the War. Red and green, interwoven in some piece of old knitting or the stripes on a cleaning lady’s shopping bag. Red with a white stripe, or yellow with a black flash, on railway signals. Red and blue, in triangular segments, on the caps of the town primary school boys. (This later led to some confusion about primary colours.) Muddy shades of felty purple, brown, green, pink, yellow and maroon, on a pole outside a newsagents; in the backdrops to some shop windows, which seemed to have been there for ever; in the Battenberg-cake pattern of square panes in a window in the public park shelter; in the pre-war clothes that many women still wore. The page of flags of the world, some of them out of date, at the beginning of Bartholomew’s Atlas. Billowing white cumulus against a blue sky, perhaps in Book One of Wheaton’s Rhythmic Readers, which my mother had bought in Exeter to teach me from at home, since getting me to school seemed too difficult until I was six. Lying blissfully but uncomfortably in the tussocks of long grass in the back garden, I could see the yellow, black-centred clumps of helenium or rudbeckia that my mother called sunflowers, moving gently against a blue, blue sky, with the white stuccoed wall of a neighbouring house just visible beyond the overgrown back hedge.

Early on, there was pure sunlight. Two of the three windows of my nursery faced south, on a level with the Tiverton Borough Bowling Green across the road. Along the pavement grew lime trees with a dense, scrubby growth around the lower part of their trunks. Between these, above my window bars and the bowling-green pavilion roof, higher than the line of the Grand Western Canal which ended in a sluice gate up Canal Hill, I could see the sun beaming down like the lid of a Tate and Lyles golden-syrup tin. Or like several lids emerging one from another, in a confusion of greenish, purplish, whitish light. It was like the effect of dropping a plate into water and watching it slowly swaying and spiralling to the bottom, so that several plates, instead of one, seemed to be carrying out that complicated, slow descent.

At first, in that nursery, I was left in a playpen with a row of beads, black, pink, white, green, let into it for visual stimulus. Once I could climb out of this, my mother locked me into the room in the mornings with a hook and staple fixed high up on the door. Bored with my own company, and disliking the texture of the crumbling, elephant-coloured cork linoleum surrounded by black-stained floorboards, I used to shake the door until the hook unscrewed itself and slip out on to the cold, brown, cracked landing linoleum, so shiny with age that one could sledge about on it on mats. My mother would be downstairs in the kitchen, washing up the breakfast things, making rabbit pie for lunch, or prodding the washing as it seethed in a tub on the Cookanheat coke range. My father would be tapping at his typewriter in the ground-floor front room he called the Office, or, for a time, writing unpublishable novels with a dip-pen in green ink in a rented room over a shop in the town. My sister was at her convent day school; my brother away at boarding school. Because my parents hardly ever visited him, it was easy for me to forget him until the day he was due to come home, when a tremendous yearning set in. ‘When will he be here?’ ‘Soon, soon.’ At which ‘soon’ and ‘spoon’ became confused, so that bright, battered silver teaspoons stood for my brother’s arrival at the station and five-minute walk to our back gate. Watching out for him to come up the cinder path beside the vegetable beds, I constructed a bird’s nest on the ground out of wisps of hay in the hope that a bird might be grateful and come and live in it.

Anon.