An Inventory

'Let in the object, and let out the sight.'

- Item. A pair of designer shoes: flat velvet mules the colour of crushed raspberries, topped with bows. Too expensive to wear outdoors, but well suited, it turns out, to adding a bit of flair to life on lockdown;

- Item. A black tulle dressing gown, the fabric spangled with tiny silver stars;

- Item(s). Postcards of my favourite Elizabethan and early Stuart portrait miniatures: a French gentleman in a teasing state of dishabille, the first two buttons of his doublet undone. A jaunty cross-dressing woman in masculine riding dress, cavalier-style locks of hair spilling from a black wide-brim hat.

I frequently think about how objects move us, condition the way we live, provoke certain behav-iours. The portable objects we carry fascinate me. Our personal archives, told by our collection of transitory things. I did bring practical things with me when came to London to stay with H during lockdown, but I made these exceptions. The other occupants of the house had recently moved out, leaving many of the rooms bare. It was important to bring something of myself into the flat.

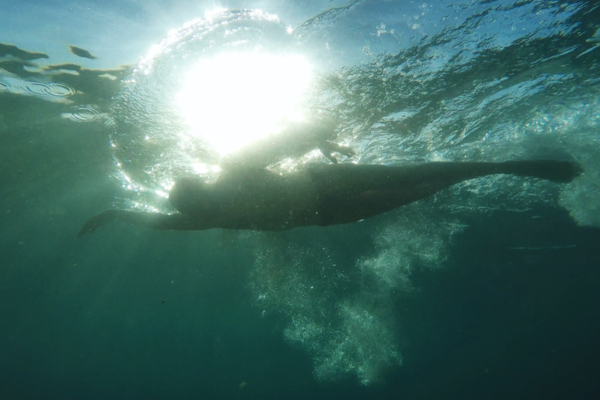

Lilacs, a glass coffee jug, a lemon, a basil plant. I find the domestic environment during a pan-demic takes on the slightly surreal quality of a seventeenth-century still life, with its mixture of shadows and glints of bright sunlight. Life imitates art, or is it the other way around? I observe H’s own things where they sit on his windowsill and bookshelves in the hope of gleaning new things about him. There are poetry anthologies. Novels. Studies on the lyric, correspondences be-tween modern poets. Browsing a person’s books is like checking for mutual friends on social me-dia: who does he spend his time with? I recall the shelves in the bedrooms of former boys: Russian novels and finance books, or architecture coffee table books.

My favourite objects these days are those that do not reflect separate lives, but a coming togeth-er. A crumpled receipt from the train journey H and I took in Switzerland in February, evoking a brilliantly sunny day when we took a walk along the Montreux Riviera, the mountains awash in a palette of blues so crisp they looked hyperreal. A dried rose from a recent anniversary. A page from the Jacobean-style masque we penned a few weeks ago in a fit of inspiration, or maybe just boredom (the WiFi stopped working), in which the evil goddess Corona descends upon earth to infect its inhabitants, ushering chaos in her wake. There were winged cherubs, jaguars, and a lot rhyming couplets.

I am drawn to interior lives: of the self, of the places we physically inhabit. Early modern authors evoked this relationship frequently. ‘Man’s Bodie is like a house’, wrote the emblematist Francis Quarles. ‘His greater bones/Are the main timber…His heart/Is the great chamber, full of curious art…His eyes are crystal windows, clear and bright:/Let in the object, and let out the sight.’ Also typical of Renaissance authors, Quarles ended his poem with a meditation on death. If only we were ‘ruin proof’, he wrote. ‘Or by nature strong enough/To conquer time, and age’. A pandemic seems to invite reflections on ruins and decay. Like a peach tottering on the edge of a table in a still life painting, we feel poised on the brink of loss. Saddened, even, by the beauty and desirabil-ity of a life destined to topple and bruise. H is more iconoclastic than I am. Less enchanted by the presence of things. But I see them as a way to salvage something from the wreck of time. Such acts of recovery or of preservation tell us something about the person, not just the thing. What we see reflected in objects around us are imbued with the value we choose to give them. So wrote Phineas Fletcher in 1633: ‘As some Optick-glasses, if we look one way, increase the object; if the other, [they] lessen the quantity. Such is an Eye that looks through Affection. It doubles any good, and extenuates what is amiss’. I may have amplified the good I see in a lilac, or H’s train receipt, but such is the eye that looks…

Lauren Working is a historian at the University of Oxford. She Tweets at @lauren_working